Treated conditions

Home » Areas of expertise » Hydrocephalus

Treated conditions

Hydrocephalus

In order to understand the pathophysiology of hydrocephalus, it is necessary to mention some brief anatomical notes.

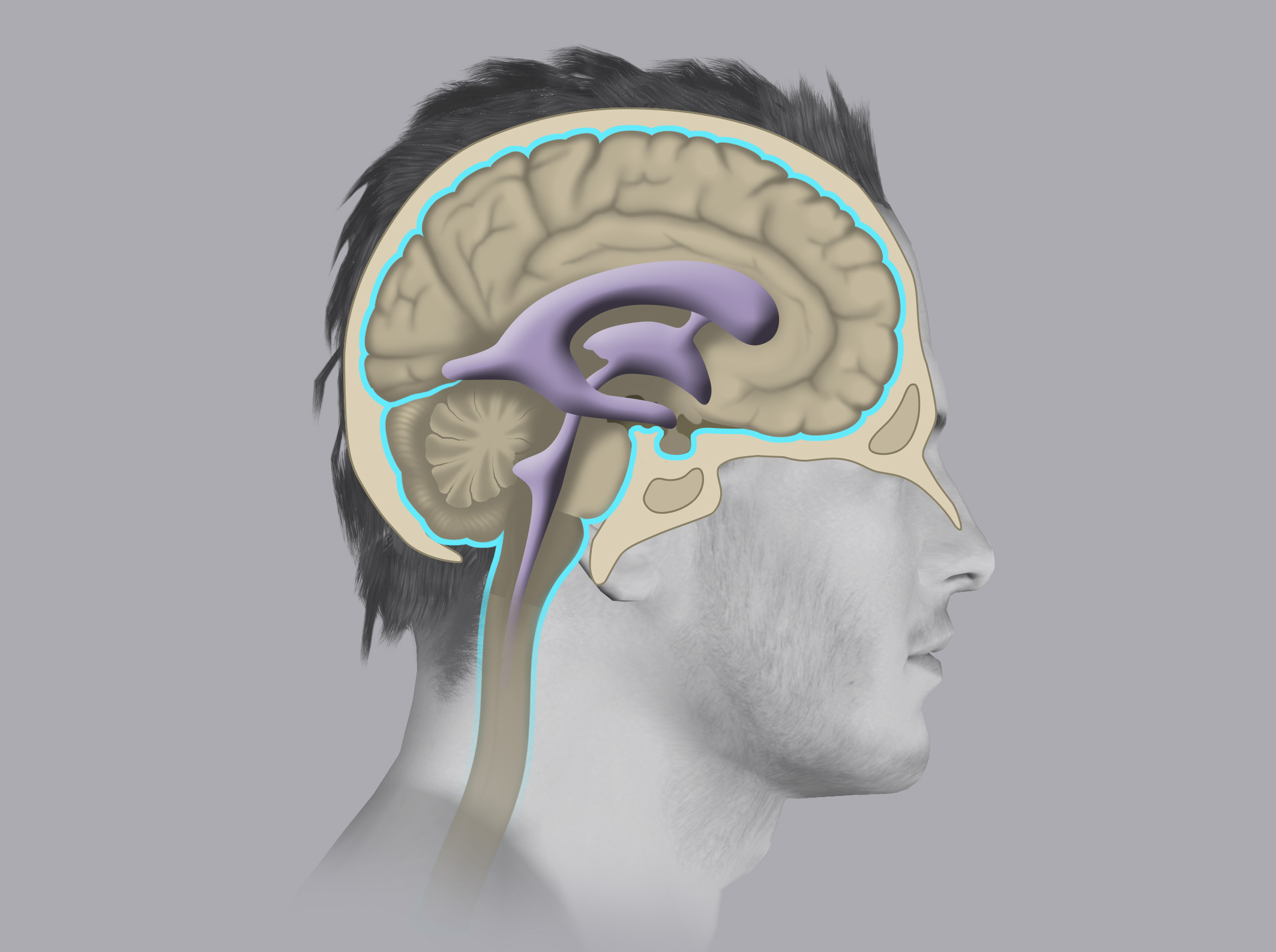

The central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) is immersed in the Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (spinal fluid), which performs various functions, some of which are: mechanical protection and enabling the exchange of substances with the nervous system.

The CSF is continuously produced by structures called the choroid plexuses, which are located in cavities known as the ventricles of the brain. From there it flows to reach the surface of the brain and spinal cord where it is then reabsorbed by other structures defined as the Pacchionian granulations.

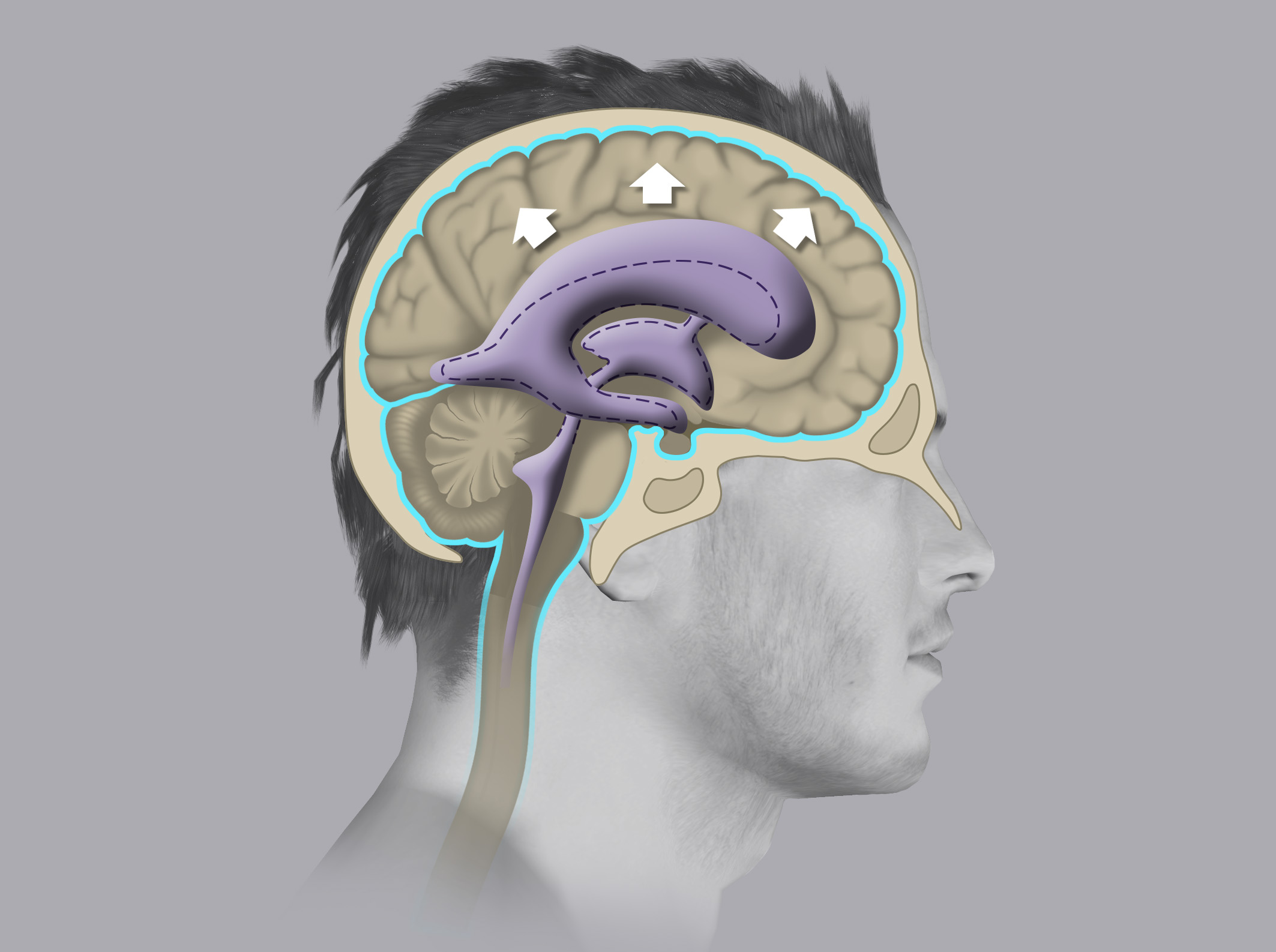

Hydrocephalus is defined as the dilation of one or more ventricles due to excess CSF accumulated in them.

Hydrocephalus may occur due to an excessive production of spinal fluid, a reduction in CSF reabsorption, or due to an obstruction of the circulation of the spinal fluid itself, with consequent accumulation of CSF upstream of the obstruction.

Hydrocephalus may occur in a short time (acute hydrocephalus) and endanger patient’s life if not promptly treated or it may develop very slowly (normal pressure hydrocephalus or chronic hydrocephalus).

Acute hydrocephalus usually develops following a cerebral hemorrhage and needs to be treated urgently by positioning a small catheter inside the right lateral ventricle in order to drain out the excess spinal fluid and normalise the intracranial pressure (EVD- external ventricular drain).

In this chapter, we will discuss the Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH) in detail.

Symptoms

The classic symptomatology of NPH is defined as Hakim’s triad and includes:

- Gait disorder (short shuffling steps and unstable walking)

- Cognitive disorders (especially memory reduction)

- Urinary incontinence

In view of this clinical scenario, albeit similar to that of other diseases typical of old age (first of all Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease) the physician should suspect NPH and proceed with the appropriate diagnostic tests.

Diagnosis

A patient presenting the symptoms of Hakim’s triad must perform an encephalic CT scan and CSF flow MRI.

Radiological tests can reveal the dilation of the ventricular cavities, but it is best to integrate the neuroradiological examinations with a CSF tap test: the patient performs some cognitive and gait tests, then he undergoes a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) through which about 40 cc of spinal fluid are removed. After about 1 hour, the patient repeats the cognitive tests previously executed and any improvement in the performance is assessed.

The tap test is performed in day-hospital treatment.

When there is a match between symptomatology, radiologic exams, and tests, then a NPH can be diagnosed.

Treatment

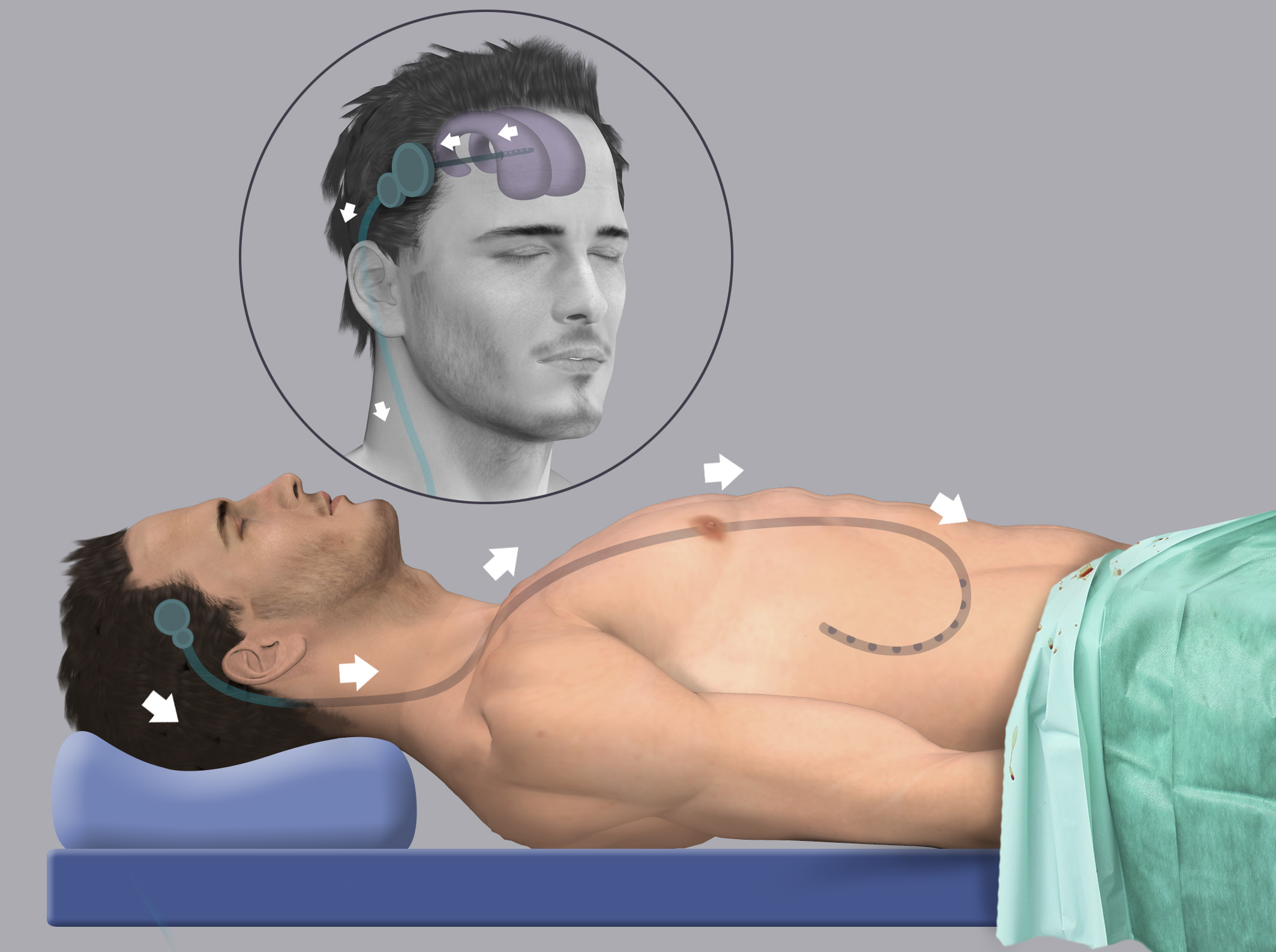

The treatment of NPH is surgical and it is defined as ventriculo-peritoneal (VP) shunt.

It consists of introducing a catheter in the right lateral ventricle and connecting it through a valve to another longer catheter, the end of which is placed in the peritoneal cavity.

The excess of spinal fluid will flow into the peritoneum, where it is reabsorbed and eliminated.

It is a safe procedure, which requires 4 days of hospitalization and leads to surprising clinical improvements.

In the months following the surgery, patients have to undergo some routine check-ups to assess the correct functioning of the shunt and evaluate the adjustment of the valve calibration based on the radiological images and the symptomatology.

In fact, the valves can be calibrated in just a few seconds with an external magnet, in a non-invasive way.